Kevin Magnussen can joke about it all now.

After a Miami Grand Prix punctuated with 65-seconds worth of penalties for leaving the track multiple times in a kerfuffle with Lewis Hamilton and causing a collision with Logan Sargeant, Magnussen was once again called to the stewards after qualifying for the Emilia Romagna Grand Prix, only this time because Oscar Piastri impeded him.

“Nice to see the stewards again and make sure they are doing alright,” he said.

Magnussen, on the verge of a race ban, drove to P12 after starting P18, overtaking two Alpines, two Saubers and Daniel Ricciardo’s VCARB, clearly showing he’s a better racer than his scrappy Miami drive. But however gnarled his race craft, Magnussen drove as if the stakes were high—like he really had something to fight for.

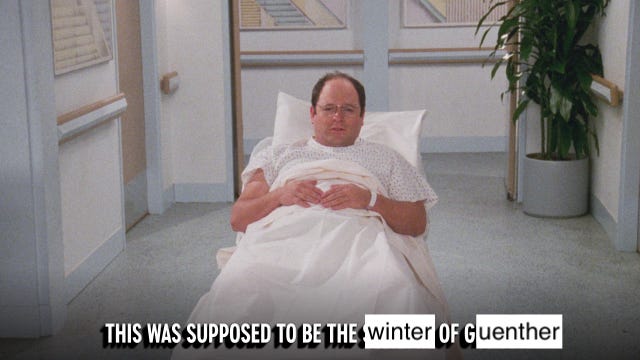

Under the new leadership of team principal Ayao Komatsu, he really does. Five months into his tenure, Komatsu, an engineer with Haas since its 2016 inaugural year has been a strong foil to former brass Guenther Steiner: By late March, he announced that Haas—having made a better-than-expected impression in season’s early days–would move up its upgrade schedule. Seven races into the season, Haas has scored seven points, compared to the 12 total in 2023. While these feats can’t totally be chocked up to a new guy at the team’s helm, there’s another thing to be said for Komatsu: You don’t see him much in headlines.

Last week, Haas sued Steiner in the Central District of California over trademark infringement, alleging that he “authored, marketed, promoted, sold, distributed, and profited from a publication titled ‘Surviving to Drive,’” essentially that his memoir used Haas’s imagery and trademarks for his own financial gain. But the lawsuit was a returning blow to Steiner, who, only three days earlier, sued his former team for allegedly refusing to pay him commissions owed from 2021 to 2023 after his January termination, which would have violated his contract.

The legal implosion obviously doesn’t reflect the initial narrative Steiner and the team projected at the time of Steiner’s firing: “Being free is always fun,” Steiner told the Athletic. Being embroiled in multiple lawsuits—including one you’ve instigated yourself—isn’t my idea of free, regardless of network television promises of producer roles or a potential future in commentating.

But Komatsu—who has been a presence in Formula 1 for over 20 years, first as a tire engineer for British American Racing before becoming chief race engineer at Lotus—has done his talking on track. His drivers have scored in four of seven grands prix, with Nico Hülkenberg making consistent Q3 appearances. Waiting in the wings following his departure is Ollie Bearman, a bright prospect for the team. Adjacent to F1, Haas can be taken seriously: Chloe Chambers, Haas’s American F1 Academy driver representing the team, scored her first podium in the series in Miami, earning P3 in Race 1 and following the performance up with a P4 in Race 2.

Sure, the team has gotten a kick in the pants to compete thanks to a tightening F1 midfield, but its biggest threat might come from off the grid. Motorsport legend Michael Andretti has held fast against F1 and Liberty Media’s persistent rejection of his bid to enter the sport. With an Indianapolis-based factory and deep roots in IndyCar, an Andretti team in F1 would represent an American powerhouse in the sport, potentially dwarfing the North Carolina-based Haas team yet to score a podium in eight years.

Steiner blamed the team’s lack of performance on owner Gene Haas, whom he said refused to properly invest in the team. Indeed, the owner's wallet is the final piece of Haas’s puzzle: Haas has turned down investors who have approached him with Alpine-line deals, arguing the partnerships would not be a good fit for the team.

“They expect a 15% rate of return every year,” Haas said. “Give me a 15% rate of return and I have a couple of hundred million dollars I’ll give you! They have high expectations; they have all kinds of rules.”

Following Steiner’s departure, Haas said he would invest in a new motorhome for the team, a symbolic gesture to illustrate his intention to further invest in the team. But Steiner, despite pushing for more of Haas’s dollars—and perhaps oblivious to his own leadership of the squad—has also said the team will need more than funds to bring it into contention: “It’s not about money,” Steiner said. “It’s about a business model.

On-track debris:

Dedicating some space here to chat about Max Verstappen’s sim racing obsession. Just six hours before lights out in Imola, Verstappen was participating in a 24 hour Nurburgring iRacing event. His Redline team even joked that he was free to participate in his F1 “hobby”. But Verstappen finished the Emilia Romagna Grand Prix just seven tenths ahead of Lando Norris after struggling with the car all weekend. It wasn’t his fault—Verstappen was miles ahead of teammate Sergio Perez, who finished in P8, but would his sim racing habit draw a different kind of attention had lost the race to Norris?

Verstappen, as a three-time world champion, is not only tasked with driving his car well, but with representing his sport. This isn’t a chastisement against Verstappen at all. But along with Verstappen hinting at his own retirement, his sim racing streak certainly indicates energy elsewhere—a stark difference from the lengths drivers like Nico Rosberg would go to to achieve race wins over rival Hamilton, cutting down his socks and parts of his car seat to gain fractions of seconds on track.